Through Good 360 and the Center’s cornerstone Nebraska Truckloads of Help program, Lincoln’s Center For People In Need receives thousands of book donations from participating non-profits and national companies alike, helping put free books in the homes and schools of low-income and high-need families throughout Nebraska.

These are the stories of some of those stories.

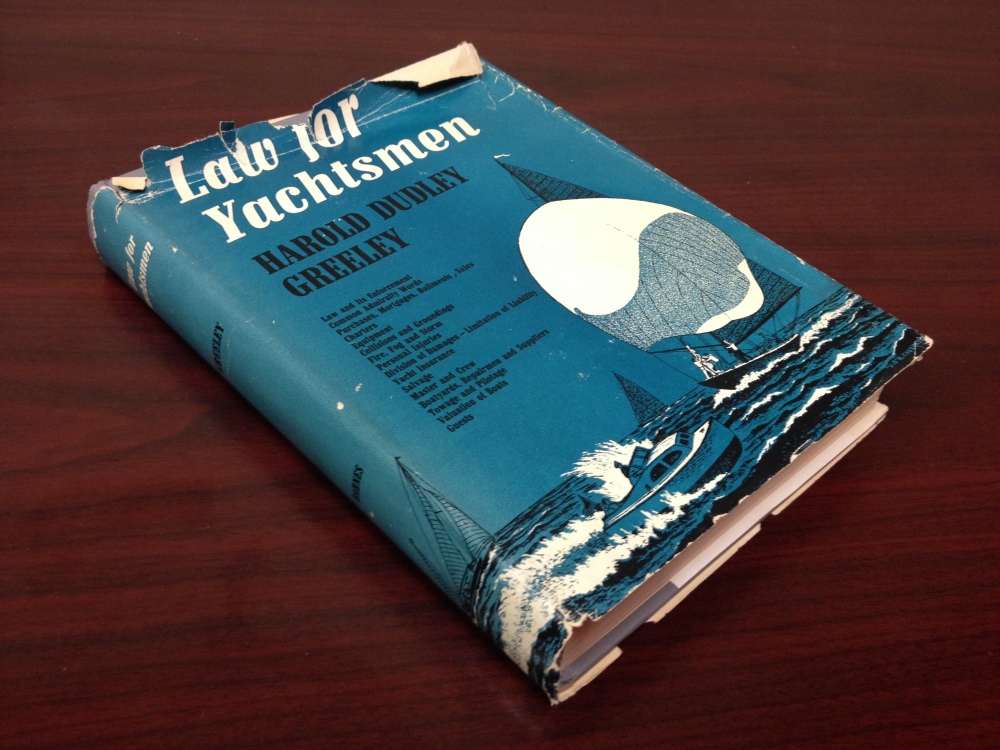

Today we take to the high seas with Harold Dudley Greeley, author of 1952’s seminal Law for Yachtsmen – which originally retailed for $4.00.

H.D. Greeley appears to have published extensively on legal issues in business accounting (constructure; illustrative,) but comes to us today in the raiment of the pleasureboater.

Greeley’s account of the state of the motor boating art at the resolution of World War Two in Britain can be viewed as a towering monument in the field of admiralty law writing for commonfolk: the plight of so many living year-round on yachts and motor boats, quietly away from the ruined cities of England – and with so few dock slips in decent repair – reverberates through Greeley’s work.

Clear, denim shirtsleeves analysis of naufrage is Greeley’s forte – his wartime writing heralds an uncompromising yet empathetic creative voice, a Frank Capra in boat shoes.

Note the inner jacket leaf, which cautions that the book is not intended to be a substitute for a lawyer – in several places it stresses the unwisdom of trying to handle one’s own case at law.

To wit:

“An unusual explosion was reported in a cargo case which might occur on a yacht. A quantity of naphtha soap, securely wrapped, was stowed in an enclosed compartment. Vapor given off by the soap, despite the wrappings, became mixed with air to form a highly explosive gas, and this was touched off by a spark, caused probably by faulty insulation. Reconditioning work on a motorboat hauled out and shored up has a fire hazard which should not be ignored. In one situation varnish was being removed from woodwork by the use of a volatile liquid varnish remover. Cotton waste soaked with benzene was used to wipe off varnish remover and then thrown on the deck. Other workmen were removing paint with an open-flame torch, and a serious fire was started in the cotton waste. Eternal vigilance is the price of safety as well as of liberty.

Greeley, “Law for Yachtsmen” (p. 119; ref. International Marine Co. v. Fels, 164 Fed. 337; 1908.)

Or these tales of salvage and damnation of human life:

“Today, the U.S. Code prescribes: ‘Salvors of human life, who have taken part in the services rendered on the occasion of the accident giving rise to salvage, are entitled to a fair share of the remuneration awarded to the salvors of the vessel, her cargo, and accessories.’ It should be noted that this statutory extension of the law does not give salvors of life any direct award but entitles them merely to share in the award of other salvors who in the same operation have succeeded in salving property. This once led to a shocking contest in inhumanity. Two tugboat captains argued for twenty minutes as to which should leave his salvage work on a burning steamer in order to take to shore an injured seamen who at that time was slowly bleeding to death. Finally one of them lost the argument and took the dying man ashore, thus reducing his share in the award to his brethren who had kept their eyes on the main chance and had refused to be diverted from the salvage of property.

p. 187; ref. The William Rockefeller, 55 F. (2d) 904

“Of peculiar interest to operators of small motor craft was a more brutal disregard of human life by the captain of a foreign freight steamer. Two men started to run a small motorboat to a point near Coney Island, New York. They expected that the run would take less than an hour and it didn’t occur to them to have either fresh water or food on board. Their engine broke down, they didn’t know how, or were unable, to signal for help and they drifted to sea. After drifting for six days without water, food, or shelter, they were sighted by the steamer which saw but ignored their frantic signals and left them to drift for two more days before a Coast Guard cutter picked them up. The steamer could have rescued them without the slightest risk and with but a very short delay. One of them men survived long enough to sue the owners of the foreign steamer, but he failed to recover damages because the court found no way to hold the owners financially responsible for the atrocity committed by their captain.

p. 187; ref. Conte Biancamano, 71 F. (2d) 146

The covers of the book are waterproof so that it will not be damaged by rain or spray if taken on a yacht.

One might wonder how this book ended up in landlocked Nebraska, 900 miles from the nearest major sea…500 miles from the nearest Great Lake…